Brief History of the Border

Burma/Myanmar regained its independence from Great Britain in 1948 and has struggled to achieve peace and unity in the course of almost eight decades since.

At the time of independence, large swathes of the newly emancipated former colony had never been under the full or direct control of central administrations. In 1949, the Karen National Union (KNU) entered into a rebellion against the new government and over time many more ethnic armed organisations and other groups followed a similar path.

During the latter half of the last century, extensive territories in the southeast of the country neighboring Thailand were largely controlled by indigenous ethnic nationalities, predominantly Karen/Kayin, Shan, Karenni/Kayah, and Mon, who had established de facto autonomous states.

During the mid-1970s, however, the then military government made significant advances in the region.

The KNU was gradually pushed out of many of its former territories and back towards bases on the border with Thailand.

For several years, dry-season offensives by the Burma/Myanmar Army sent refugees from Karen areas into Thailand, but only temporarily; the refugees returned home in the rainy season when the Burma/Myanmar Army withdrew.

This pattern changed significantly however, in the following decade.

A Decade of Refugee Flows (1984 to 1994)

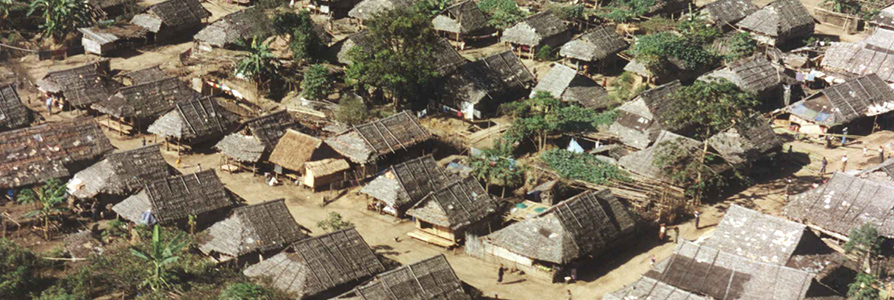

In 1984 the Burma/Myanmar Army launched a major offensive against the KNU that resulted in about 10,000 refugees fleeing into Thailand.

Unlike previous offensives, on this occasion the army was able to maintain its front-line positions, which meant the refugees had to remain in Thailand.

Over the next years the army continued to launch annual dry season offensives in which it took control of new areas, established new bases and built new supply routes.

Many more refugees were pushed into Thailand.

The border was further impacted after August 1988, when people in Burma/Myanmar rose up against the then military regime. Millions, including student activists, took part in mass demonstrations. Daw Aung San Suu Kyi emerged as a charismatic leader. The army launched a crackdown and thousands were killed on the streets before the uprising was crushed on 18 September.

During the crackdown and as a result of it, around 10,000 people, including student demonstrators, fled to the border with Thailand.

They established offices at the KNU headquarters at Manerplaw and more than 30 small ‘student’ camps were established along the border. Many of the new refugees soon returned home and by the following year the number of ‘students’ on the Thailand border had declined to around 3,000.

In 1990 the ruling State Law Order and Restoration Council (SLORC) conducted a general election which was overwhelmingly won by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD).

However the NLD was not allowed to take power. Elected MPs were imprisoned or intimidated and more people fled to the border to form a government-in-exile.

By 1994, the number of refugees in camps in Thailand had reached about 80,000.

1995: The Fall of Manerplaw

In January 1995 the Burma/Myanmar Army overran Manerplaw with the assistance of a breakaway group, the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA), and more KNU bases were lost soon after.

The following year the SLORC broke a short-lived cease-fire agreement with the Karenni National Progressive Party (KNPP) and similarly overran its key bases.

That year too Khun Sa, a leader of the Shan resistance, made a deal with SLORC which effectively allowed the Burma/Myanmar Army access to the border opposite Chiang Mai and Chiang Rai provinces in Thailand.

The trend of increasing losses of territory held by ethnic nationality armed groups continued in 1997 when the Burma/Myanmar Army launched a huge dry-season offensive which saw it over-running most of the remainder of Karen/Kayin-controlled territory along the border all the way south to Thailand’s Prachuap Khiri Kan province.

In that year, the number of refugees from Burma/Myanmar in camps in Thailand increased to 115,000.

Meanwhile, as the Burma/Myanmar Army took more control of former ethnic territory it launched a massive village relocation plan aimed at bringing the population under military control and eliminating remaining resistance.

Thousands of villages were destroyed and hundreds of thousands of people displaced.

By 2005, the numbers in the camps in Thailand peaked at 150,000 and a programme of resettlement to third countries began.

In 2011, Burma/Myanmar saw dramatic political changes and the beginning of quasi-civilian rule.

Ceasefires were agreed with many armed groups, including the KNU, and a peace negotiations process was initiated with armed groups.

The process has continued slowly under the new NLD-led government which was elected in a landslide in 2015.

For the first time in decades there was the possibility of an end to conflict, and for refugee return.

A Brief History of TBC

1984: Response to a Crisis, and a Mandate

Thailand was already host to large numbers of refugees from Cambodia and other countries of Indochina when the first major influx of Karen people from Burma/Myanmar arrived on its western border in 1984.

The Thai Ministry of the Interior (MOI) requested agencies working with the Indochina refugees to provide emergency assistance to the new arrivals who had landed in Tak province.

A number of Bangkok-based Christian agencies responded and formed a consortium which soon became the main provider of food and shelter to the refugees from Burma/Myanmar.

The Consortium of Christian Agencies (CCA) evolved and changed as an organisation over the years. This was reflected in a number of name changes; first, in 1991, to the Burmese Border Consortium (BBC); second, in 2004, to the Thailand Burma Border Consortium (TBBC); and again in 2012, to The Border Consortium (TBC).

Under policies set by the MOI, the consortium worked closely with a Burma subcommittee made up of NGOs that were members of the Committee for Coordination of Services to Displaced Persons in Thailand (CCSDPT).

From the outset, the consortium that became TBC worked through the Karen Refugee Committee (KRC), which Karen authorities had established to oversee the refugee population.

1989/1990: Expansion and New Regulations

As the Burma/Myanmar Army overran more parts of the border areas, the TBC (under its earlier names) continued to extend food and shelter assistance to the growing numbers of people entering camps in Thailand.

From 1989, it worked with the Karenni Refugee Committee (KnRC) in Mae Hong Son province, and from 1990, with the Mon National Relief Committee in Kanchanaburi province.

In 1991, the MOI gave formal approval for NGOs to work with the new populations of refugees and new guidelines were set up. These confirmed earlier informal understandings which limited assistance to food, clothing and medicine, and restricted agency staff to the minimum necessary.

Three NGOs provided assistance under this agreement: the TBC provided around 95 percent of food and non-food items; the Catholic Office for Emergency Relief and Refugees (COERR) provided most of the balance; and Médecins Sans Frontières, France, provided health care.

As refugee numbers grew, more agencies began providing services on the border.

These were formally approved by the MOI in May 1994 when the NGO mandate was extended to include sanitation and education services.

1997/8: A Role for the UN Refugee Agency

By 1997 the Indochina refugee crisis was largely resolved and the network of supporting NGOs in the CCSDPT was mainly working with refugees from Burma/Myanmar.

NGOs that had been a part of less formalized Burma Medical and Education Working Groups were upgraded to CCSDPT subcommittee status.

During the first half of 1998 the Royal Thai Government (RTG) made the decision to give the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) an operational role with the refugees from Burma/Myanmar.

The UNHCR soon opened offices in Mae Hong Son, Mae Sot and Kanchanaburi, relatively close to a number of camps. Its role was principally one of monitoring and protection.

Refugee Policy Advocacy

In April 2005, the alliance of organisations in the CCSDPT and the UN Refugee Agency began to advocate with the RTG to allow refugees increased skills-training and education opportunities, as well as income generation projects and employment opportunities.

It was argued that allowing refugees to work could contribute positively to the Thai economy, promote dignity and self-reliance for the refugees, and gradually reduce the need for humanitarian assistance.

The following year the MOI gave its approval for NGOs to expand skills training with income-generation possibilities.

The RTG also made commitments to improve education in the camps and to explore employment possibilities through pilot projects. But progress was slow, and in 2009 the CCSDPT and the UN Refugee Agency drafted a five-year Strategic Plan incorporating a coordinated strategy for all service sectors that aimed at increasing refugee self-reliance and, where possible, integrating refugee services within the Thai system.

This was presented to the government and donors in November 2009, but, while the RTG was sympathetic to the need for refugees to have more fulfilling, productive lives, the limiting policy of confinement to camps remained unchanged.

However, the objectives of the plan remained valid and proved useful as a planning tool.

During 2010 CCSDPT and the UN Refugee Agency incorporated many of the plan’s ideas into a “Strategic Framework for Durable Solutions” to be a guiding framework for planning in all sectors. A tool to monitor short-term progress towards the framework objectives was developed in 2011.

2010: Political Change in Burma/Myanmar

In 2010 a quasi-civilian government was elected in Burma/Myanmar and soon after, most ethnic armed groups agreed ceasefires with the administration and began to take part in a nascent peace process.

Under the new NLD-led government elected in 2015, tentative peace negotiations continue.

For TBC and the organisations working with refugees, the “Strategic Framework for Durable Solutions” has been reoriented, shifting the emphasis from self-reliance in protracted asylum in Thailand to towards preparedness for a voluntary refugee return.

In 2017, as well as continuing to support the nine camps in Thailand, TBC was further developing its Burma/Myanmar programme.

This work focuses on supporting the recovery of conflict-affected communities, improving their socio-economic situations and building preparedness for the potential return and integration of displaced communities when conditions are suitable.

Read More on TBC:

The story of how TBC became involved on the Thailand and Burma/Myanmar border can be found in the report “Between Worlds, published in 2004 and available in hard copy at the TBC head office.

The personal stories of hundreds of people involved in the camps over a period of twenty-five years can be found in the book “Nine Thousand Nights: Refugees from Burma, A People’s Scrapbook’’, published in 2010, which is also available in hard copy at the TBC head office.